Much is said, written, and published about accountable care organizations (ACOs), roadmaps, and how to effectively navigate the field: the importance of best practice protocols, Lean principles, standard work, and analytics. However, not much is discussed about the fundamentals of developing the requisite models for access and primary care, not to mention the landscape design of the functioning provider network.

At the other end of the spectrum, there’s much discussion on diverting patients from the emergency department (ED) to lower cost settings and the “right care, in the right setting, at the right time.” But one is hard-pressed to find dialogue on an organizational approach to the design of primary access for people seeking services—whether in sickness or for health.

Abundant information is readily available on how organizations should approach this transitional time of living in the fee-for-service world and preparing for a value proposition, be it capitation/bundling/risk, sharing/gain sharing, etc. For example, Intermountain Health in Salt Lake City, Utah, put a best-practice protocol in place that improved its newborn delivery outcomes but cost them over $2 million in revenues it would have generated under current reimbursement methods. In an attempt to reduce costs, another health system piloted use of a different brand of procedure disposables which, in the trial period, resulted in an increased complication rate. The complications generated additional revenues (bed days and acuity of services), which spurred a crucial conversation among finance, purchasing, and clinical leaders.

Conversely, go in search of education about the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model, and there’s much to be found: PCMH recognition, criteria, design, and the importance of success to lower cost. However, there’s not a lot said about whether each physician who leads a team is primary care focused or whether each physician leads a team at all. Still less can be found on whether each location is a team or whether each network should work as one team. Many treat PMCH as a destination in their journey rather than as a signpost or mile marker. The point of PCMH is not to create momentum to retry the failed gatekeeper primary care provider (PCP) approach of the 1980s health maintenance organization (HMO).

Terry McGeeney, M.D., M.B.A., past president of Transformed, a for-profit affiliate of the American Academy of Family Physicians, makes the point that PCMH is not a plumbing fixture that is installed (recognition), and then you’re finished. “The Patient Centered Medical Home is a comprehensive concept encompassing highly accessible, coordinated, and continuous team-driven, physician-led delivery of primary care that relies on the use of decision-support tools and ongoing quality measurement and improvement.” (Y, Adashi,MD, H.Jack Geiger, MD, and Michael D. Fine, MD New England Journal of Medicine 362:2047-2050,: June 2,2010.

The Move to Patient-Centric

Health care is moving from a hospital-centric model, and beyond provider-centric and even ambulatory-centric, to a patient-centric design imperative. PCMH is a key, but what do primary care, primary access, and network design need to be to decrease cost, ED use, support population health, and realize the precepts of Don Berwick, M.D.’s “Triple Aim” (care, health, and cost)?

Integration of retail resources, retail clinics, and urgent care in a primary care strategy will create a differential advantage in markets while creating a barrier of entry for boutique operators and expanding primary care network and primary access capacity and capture. This will fulfill market growth and capture aspirations through improved access to clinically integrated and coordinated care.

Therefore, we need to develop and culturally engage a broad perspective of the team that focuses on capacity and clinical quality—outcome metrics care management opportunities—as opposed to individual ownership of the direct encounter. Integration of retail and other primary access components (OURHospital.com, screenings, Health Risk Assessment [HRA] programs, worksite clinics, and patient portals) will improve access and reduce costs. We must adopt a cultural and operational willingness to embed retail and urgent care as locations in a primary care, primary-access strategy. (Cultural adaptation is also needed to engage best practice-defined protocols, but that’s a separate discussion.)

Should we consider the Cleveland Clinic approach to same-day appointments? That is, call a central number, and if your physician or office cannot see you today, they’ll send you to another network office. How do they do it? Their facilities are all connected in a common electronic medical record (EMR). It’s a retail mindset, one that CVS and Walgreens have already adopted: Serve customers at their time of need and at their convenience, or they’ll go down the street.

In supporting PCMH precepts as being patient-centered, network access should neither drive people to nor through specific entry points or a defined location, but support the mandate to shorten waiting times and after-hours care. Access allows people to go where it is comfortable and convenient. Retail settings should be designed as parts of the continuum, which extends from home (IT/IS and patient portal-supported) to our offices and the ED/hospital setting. Retail settings, while serving as easy points of access, are really extensions of PCMH practices and overall network. A key function of the PCMH, then, is patient engagement and activation, without which we will not succeed.

The Need for Capture

Much can be said for changing reimbursement methods and transition from volume to value, but what about primary care and first-touch engagement/capture to a system of care? Integrated networks, whether focused on revenue in a fee-for-service environment or cost control in bundles and capitation variants, share the fundamental need for capture. We know also that out-of-pocket cost and convenience trump loyalty in even the most activated and engaged member.

Instead of PCMH, primary care networks, and “strategies,” a fully integrated system should embrace the concept of primary access as any place that can be the first point-of-contact for any patient who’s looking to receive services, whether it be via web site, a screening program, an online health risk assessment, the ED, or any other part of the network. Sharing one EMR and working as one team in support of the entire community population makes both business and medicinal sense. Each doctor or each practice then does NOT have its own unique panel of patients, forgoing the cottage industry of fragmented care in favor of a fully integrated network. In order to fully realize this opportunity, however, a cultural transformation of the health system and each physician/clinician is essential.

The Primary Access System

- Grone O. & Garcia-Barbero, M (2002) Trends in integrated care – Reflections on conceptual issues. EUR/02/5037864 Copenhagen : World Health Organisation: “Integration is a means to improve services in relation to access, quality, user satisfaction, and efficiency.”

- Naomi Freundlich and staff of The Commonwealth Fund: June 12, 2013: “Easier access to primary care is a key to both improving the quality of health care overall and reducing costs.”

Of course, to make this work requires more than integrating retail and urgent care into the primary care strategy and evolution toward a primary access system. In an effort to elevate the profile of the ambulatory aspects of their practice, specialty practices, emergency departments, and other components of the network must also transform their physician-centric mentality. In addition to enhanced access, they must adopt the culture of a shared plan of care and the technical appreciation that each provider with the patient must own medication reconciliation. The list must reflect what is prescribed and note reasons for physician changes as well as what the patient may not be taking and why (cost, side effects, something they read on the Internet) and what they are taking from nontraditional sources (meds from other family members or friends because they work for them), including what out-of-network providers are adding and changing. This needs to be attended to at each and every encounter.

Specialty practices then should change the model of care to accommodate greater access and facilitate care coordination. They should enable e-curbside consults for acuity stratification of visits and guidance, as well as virtual followups. In so doing, specialty practices are accomplishing improved access by offering e-curbside consults to support the PCP and ultimately support and become accountable for the quality of care and outcomes for people who they do not see or touch.

The e-curbside will support acuity stratification to enable the direct encounter between patient and specialist. San Francisco General Hospital’s experience has demonstrated the value that iterative communication between the PCP and specialist reviewer offer in providing specialty expertise to PCPs, which is an adjunct to affording enhanced access. Specialty practices, as well as other network providers of clinical and ancillary services, represent virtual extensions of the PCMH as components of a fully integrated accountable care network. Specialty practices and other points of access need to elevate their games in considering and developing the shared plan of care. Elevate communication in the form of synchronous or asynchronous tools. Again, shared plan of care has multiple meanings and, in this context, should refer to one shared among all network providers and consistent with patient wishes and patient engagement/activation.

While establishing this collaborative culture and commitment among doctors, advanced practice clinicians (APCs), hospitals, labs, and rehab facilities, the enabling member of the team is the electronic health record—without which this cannot work. Let it be clear that we may neither rely solely on technology for communication nor execution: in the end, the successful execution of a project/process remains dependent on communication channels that go as far as possible to replicate the richness of collocated communication. In single locations, a shared context—cultural, organizational, functional, and technological—makes it easier to discuss (develop/advance) complex ideas, resolve problems, and develop innovations informally.

Misunderstandings and Tension

Because communication in this environment is second nature, managers tend to underestimate the challenge of scaling communication. Information and communication technologies, or electronic medical records (EMR), have a role to play, but those tools should not be over-relied on as they tend to make differences between locations, leading to misunderstandings and tension. These electronic exchanges are then captured in real time in the patient EMR.

Another multi-use term is “navigator.” Unfortunately, the Affordable Care Act has identified it, codified its use by ascribing dollars to it, and defined the role as one which helps people engage health exchanges and similar “insurance” products. In the clinical world, the navigator role is essential to facilitating patient engagement and coordinating care through the matrix of integrated providers and their technology-supported system. In adopting the Intermountain system discipline, the protocols established are based on data, and IS/IT tools will measure adherence and performance as well as apply analytics in support of the new culture.

These technology tools need to be fully leveraged to provide decision support of best practice protocols (and their adherence), act without the direct click by a clinician, and generate automated orders (or reminders) in support of closing gaps and generating patient engagement and activation. Pennsylvania’s Geisinger Health System’s “anticipatory management” program is a model to emulate. In it, clinically integrated/accountable models of care are not only an extension of PCP, but contain one population of patients, with one network of providers, including many locations of varying capability.

Access, Convenience, Cost

Dr. Berwick coined the term “Triple Aim”: improving the individual experience of care; improving the health of populations; and reducing per capita costs of care for populations. Thus, the three caveats of success in achieving good outcomes: access, convenience, and cost.

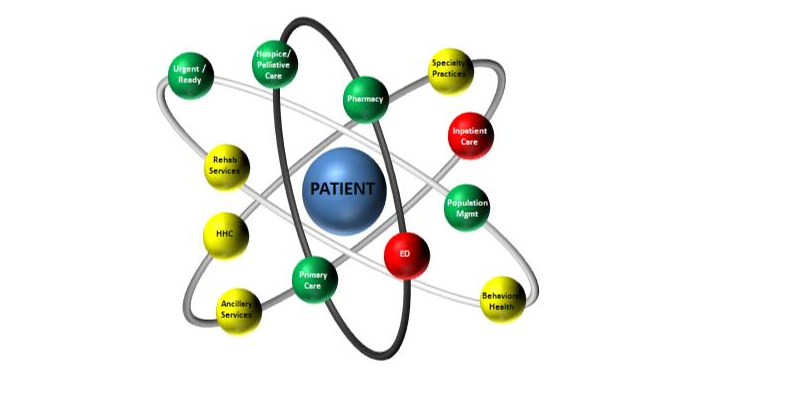

Sometimes, a visual nurtures the acceptance of a concept and allows for innovative interpretation (see Figure 1), not just for the conceptual goal but also process. If we begin with the house, which depicted the early PCMH concept, and move toward the pyramid and orbit designs, we see that we continue a hierarchy of segmented connectivity through intermediate channels and steps. Our aspiration is to become patient centric and offer primary access through any of our locations and convey the obligation for convenience.

Let us then offer a new term: the “Active Health Network.” Postulate that we evolve to realize the vision of a comprehensive network of clinical and ancillary resources for one team, which supports our shared population of patients in sickness and for health.

“Doing what is right to improve the patient experience is increasingly complex, but every indicator suggests that a seamless delivery system is the solution.” (A.R. Kovener “What more evidence do you need?” Harvard Business Review May 2010)

Steven L. Delaveris, D.O., is vice president of WellSpan Health in York, Pennsylvania, and head of the Department of Internal Medicine at York Hospital.

Figure 1: Moving pyramids