A model cell, in the world of performance improvement, is a proof of concept that demonstrates real culture change and real results. 1 It is a testing center to experiment with ideas and put new concepts into action, and the front line of debates between early adopters embracing change and skeptics who think the old ways were good enough. 2 In this context, WellSpan Health’s Central Alert Team (CAT) is indeed a model cell for a novel care approach—where data is applied to impact the care of individuals and populations, reducing reliance on the point of care.

WellSpan Health’s (WSH) wildly successful initiative to improve the care and treatment of people with sepsis is recognized nationally, with several health systems contacting us to request a deeper dive into our tools and processes. All WSH hospitals have experienced measurable outcomes that have demonstrated national top decile performance in the critical quality objectives of overall mortality and in the sepsis treatment bundle compliance and timing. However, history and the literature support the reality that simply implementing alert algorithms and mapping workflows will not directly lead to the outcomes successes we achieved, which include measures of morbidity, mortality, utilization and finance. Rather, the “new care model,” as it has been developed at WSH, is the key to success. Benefits of the care model included early recognition, early acuity stratification, timely treatment, and improved documentation.

Before delving into the details of the novel care model, let us first consider the traditional model of care. This model is built around and reliant upon the provider encounter and astute clinician. Care opportunities are identified when a patient seeks out medical care—which may range from an office visit, to a hospital admission. Piecing together the picture can prove to be quite challenging. Although paper records are inefficient and readily accessible only at the site they were housed, digital records are often unnecessarily bloated and lacking truly relevant, useful details. Much more time of an appointment is consumed with sifting through and organizing information in the digital record, with less time spent actually engaging with the patient. Advisories, although intended to draw clinician’s attention to important gaps, instead add to the chaos if too numerous or prove invalid. A team at Mayo Clinic found that found that how much time an individual spent doing computer documentation was one of the strongest predictors of burnout. Atul Gawande mused that after his system’s transition to Epic, he “has come to feel that a system that promised to increase my mastery over my work has, instead, increased my work’s mastery over me.”

Indeed, our own experience with leveraging EHR advisories to improve diabetes care provide a case study in the shortfalls of intersecting them with our traditional care model. When implementing a new EHR vendor, we decided to pilot a series of clinical decision support tools in five primary care practices to draw providers’ attention to care gaps to ensure patient care was aligned with established best practices for testing, medication management, and plan of care adjustment. Over the course of the pilot, 2446 advisories were triggered—and only 15 were acted upon, an abysmal rate of less than 1%. We found that when a provider opened a chart during a visit, they were presented with a long list of advisories with those related to diabetes at the very bottom. Overwhelmed with addressing so many with the patient in front of them, the provider almost always ignored them. Care gaps persisted.

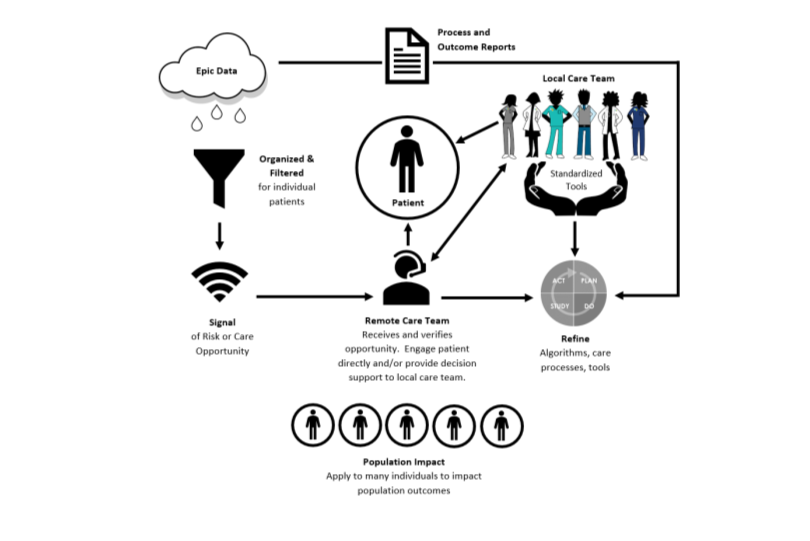

In our new care model, focus is shifted away from the point of care and to the patient and their specific care needs, when they need it. Epic data can be organized and filtered by best practice advisories, reporting tools, or predictive analytics modules to identify risk and potential care opportunities. In the case of sepsis, this is accomplished by firing of Best Practice Advisories (BPAs)—based on Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, endorsed by the sepsis CET, and undergoing constant refinement based on user feedback. Signals of potential risks or opportunities, in this case indications that a patient may have sepsis, are received by a remote care team—the CAT—who review and verify the opportunity. Once validated, the remote team connects with the local care team as needed to ensure awareness and provide decision support. The care team has appropriate clinical background and specialized training to be able to perform these functions. CAT RNs are seasoned emergency department and/or intensive care unit nurses with specialized training in sepsis and remote monitoring—giving them clinical credibility with the bedside team and making them content experts in sepsis care. In other applications of the model, the remote care team could alternatively reach out to the patient directly to notify them of the opportunity and provide guidance on next steps. Team members could perhaps have a different clinical background/level of training depending on the need being addressed (RN, LPN, MA, tech, etc.).

By the time the signal reaches the provider or the patient, it is in a form that has been refined to something actionable. The patient receiving best evidence-based care is no longer dependent on them

deciding to make an office visit or the clinician being able to piece together the clinical puzzle in a complex environment. Local care teams experience reduced noise from alerts, and support to ensure care adoption. In the case of sepsis, the CAT acts as an air traffic controller—watching the clock, ensuring timely care is being carried out, and contacting the lab or pharmacy directly to ensure resources are engaged. Clinicians are also supported through standardized tools—algorithms, care protocols, order sets, creating a clear path to delivering the right care. Rather than seeing the patient through the lens of Epic, focused on the computer screen, the clinical team can now engage with the patient in front of them. They have capacity to engage the human skills of intuition, skill, experience, compassion, and empathy while reliably delivering good and best practices. Through this model, we have not simply leveraged technology, we have leveraged humanity. Multiplied over many patient encounters, this impacts the health of the population while shielding our clinicians from burnout associated with being screen-bound.

Figure 1: Applying data to impact the health of individuals and the population.

The introduction of the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) model of care offered great promise—leveraging team-based care to proactively manage a population of people. However, literal interpretation of the defining principle of “personal physician” and continued reliance on the point of care to address care opportunities has frustrated the opportunity to fully realize the benefit of this model. The concept of panel management, caring for a population of patients whether or not they come in for a visit, is a key change in mindset in becoming a PCMH. Care should be approached not as a string of loosely connected appointments, but rather proactive connections with patients to develop continued relationships and continuity of care—leading to higher quality, more consistent care. Kovner notes, “Doing what is right to improve the patient experience is increasingly complex, but every indicator suggests that a seamless delivery system is the solution.” The merging of the PCMH concept with our novel, data-driven care model will allow us to more fully realize our aspiration of being an integrated health care delivery system. Rather than perceiving their PCMH as visits with their primary provider, care will be seamlessly connected such that the patient views it as his medical home in sickness and for health.

Let us now consider how the sepsis model cell can be developed and spread to benefit other populations in our communities. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects approximately 14% of the general population. Earlier stages of kidney disease are often asymptomatic, are detected during the evaluation of comorbid conditions, and may be reversible. Left unchecked, the patient can progress to kidney failure, need for dialysis or transplant, and eventually death. Although the need for treatment of chronic kidney failure with dialysis and/or kidney transplantation arises in only 1% of people with CKD, it remains the most expensive of chronic diseases and reduces lifespan significantly. Failure to recognize CKD results in neglect of its consequences and complications, and late referral of people with advanced CKD resulting in worse renal replacement therapy (RRT) outcomes. Timely identification and appropriate management are key to improving both clinical and economic outcomes. Currently, identification of CKD is dependent on the patient visiting their PCP, and providers noting decline in kidney function on lab work during the visit. What if we used Epic to identify patients with an eGFR under a certain threshold who did not have a diagnosis of CKD and/or did not have a relationship with a nephrologist? These potential opportunities could be served to a care team oriented to review these cases to confirm. If a care gap indeed exists, the patient could be contacted to set up an appointment with an appropriate provider (PCP, nephrologist) for further evaluation. When the patient arrives for their appointment, they have a clearly defined care opportunity. The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guidelines offer a roadmap for management of CKD patients throughout the progression which can be incorporated into care protocols and order sets.

Much-hyped “disruptive” technology is seldom able to be disruptive by itself and requires concomitant changes in how work is performed to realize their full potential. 9 With the rise of EHRs, we have new tools at our disposal to improve care processes, but incorporating them into legacy, point-of-care approaches leads us to fail to realize their potential—and rather creating monstrosities clinicians despise. We have a tremendous opportunity to rethink “business as usual,” employing the Central Alert Team model of care as a roadmap for redesigning how care is provided in the age of the EHR. Our patients and providers will thank us.